Focus

For fun, I wrote a raytracer in Zig yesterday. It’s a port of a project I did in 2013, in JavaScript. It’s the first time in a while I’ve made a project just for kicks. If you look at the number of GitHub repositories I’ve committed to since 2013, the number is decreasing. Same with number of commits, but that’s almost entirely because in 2017 I learned how to use amend to combine my haphazard commits into logical chunks.

And, sure, another element of this trend is that I stopped working on so many tiny npm modules and instead worked on applications.

But systematic factors aside – what you see here is focus. Especially since committing to building Placemark, I’ve had too much focus. Basically all of my coding has been related to Placemark, or one of the consulting projects I did last year. I don’t really know how this is perceived. Is it obvious that Tom has fewer little passion projects than before, and is that good, that I’m focusing on the business, or something I should miss? Or, much more likely, nobody really cares either way.

I think that too much focus is a bad thing. A good environment has a mix of focus and experimentation.

Pairing focused mainline work with experiments can be a barbell strategy. Your main project might be some plain-vanilla Ruby on Rails app, but every once in a while you build something in Elixir or Clojure. Maybe you fall in love with those languages and quit your job so you can get a job writing Elixir code all day long. Or a challenge arrives that’s the perfect fit for Clojure, and you already have some experience and wisdom using it.

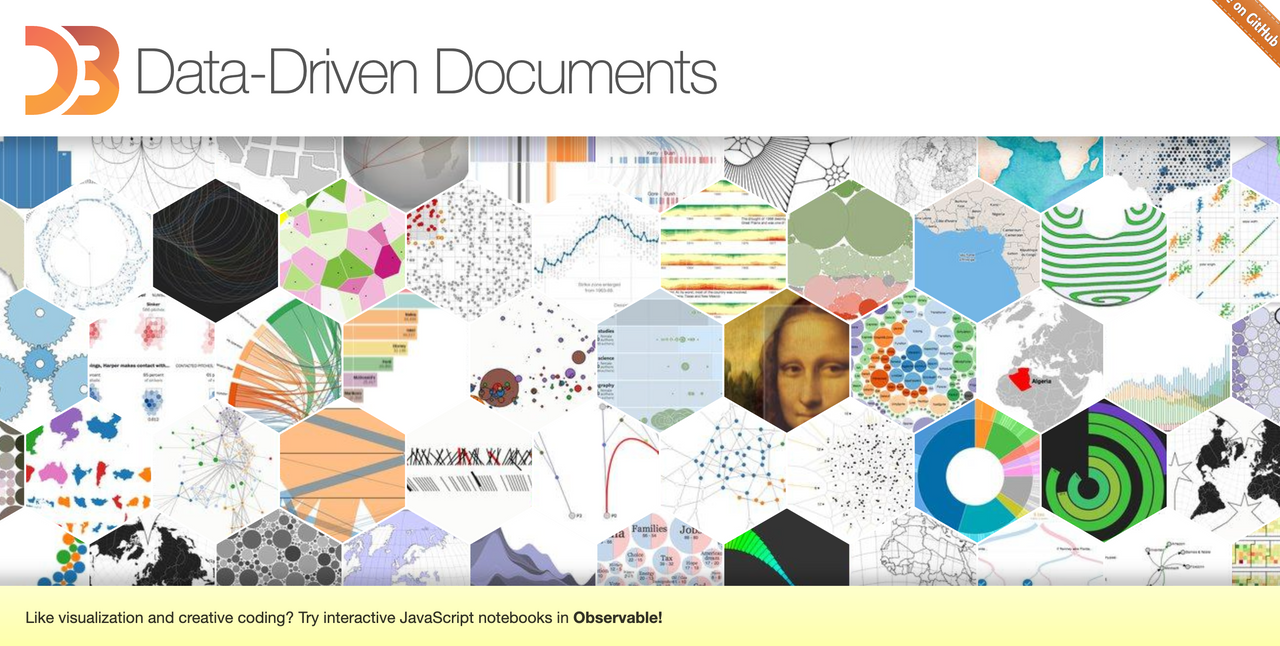

This worked for me a few times: I learned d3 for fun, then used it for work, and then ended up at the d3 company. There was no reason for the first step: some other technology would have been more practical to pump out a few data visualizations.

But this explanation is too careerist. It worked for the career because it was fun. The fun part came first.

I’ve had fun so far building Placemark. It’s been exhausting, like existentially exhausting to the point that I want to stare at a wall, but I have to fix a bug in production and write a cheery blog post for this week’s marketing. But fun, really. And educational in a way that just can’t be substituted, at all. You can read books about starting and running a company, but you won’t get 1% of the actual experience and knowledge you get by doing it. And running a company has turbocharged my personal connections with people in the industry. There are many good things about it.

Play

But what I mark as needs improvement in my workplace is play. Porting a raytracer to Zig counts. Some of the things I implement for Placemark count too, but a little less so.

The conditions for play are important.

A large part is psychological, in one’s willingness to look silly or make mistakes in public, if you do publish. I like to publish, but I have to keep doing it regularly or the fear of failure will start to creep in again. The flipside of constantly publishing, though, is that you have hundreds of projects and articles with your name on them, any one of which might get an influx of criticism or attention out of the blue, years later. I get why the kids do whitewalling and use disappearing-content networks: it’s fun to produce, but risky to have an easily-searchable history of everything you’ve produced.

And then there are material conditions. It’s striking how many people bootstrapping companies are in the same laser-focused race to revenue and product market fit that I’ve been in. It’s noticeable how a lot of the people having fun with experimental projects on the internet have hidden wealth or income that doesn’t require all of their attention.

And then there’s just age. That between the early 20s and the late 30s a lot of people’s instruments become home decor. Whether you’re jaded or just leaving some things to the youth, it’s easy to forget to be creative. It’s important to keep playing.